by Hunter Allen

Intro

Mountain biking has very specific demands that are not seen in road races, track races or even cyclo-cross.

One of the first things that I do as a coach when I have an athlete training for a specific event or discipline in cycling is to look at their event goals and then define the demands of those events.

For each event, there are general and specific demands.

A general demand might be that your MTB event is 40 miles long and it will take about 5 hours to complete. Specific demands could be that you need to go over (2) 30-minute climbs with single-track descents on the other side, there is 1 river crossing with 1 mile to the finish line, the event will be done in the middle of July and the temperature will be between 85-95F.

Once we define the demands of the event, then we can take the abilities of you, the rider, and decide how to correctly train you for that event.

Let’s talk about muscles

However, before we go too far down the rabbit hole, let’s talk about how we actually create power or watts. Let’s think about those leg muscles and all that they do, especially the quadriceps muscles (the big ones on top of your upper leg). The ‘quads’ tend to be the leg muscles that get the most work, and the sorest and the quads contribute a significant amount of work toward propelling you forward on a bicycle as they are the muscles that help to push the pedal downward on each stroke.

The quadriceps, along with the rest of the lower body muscles, need to be able to contract forcefully and slowly and contract lightly and quickly for you to become a successful mountain biker.

To me, it’s another one of the great things that makes cycling so challenging: You need to have the ability to pedal both hard and slow, along with easy and fast.

You see, the rider that feels more comfortable mashing a bigger gear most likely has more ‘fast’ twitch muscle fibers (type II), whereas the rider that likes to ‘spin’ typically uses more slow twitch fibers (type I) and this is important because if your event is going to require you to pedal hard and slow, but in training you always pedal easy and quick, then you might not be ready for your event.

This is where the ‘other’ quad comes into play.

That other quad is called Quadrant Analysis. Quadrant Analysis is a tool that allows you to understand whether you are indeed pedaling correctly for your given event.

The importance of the neuromuscular function

Riding at a cadence of 100 rpm for 3 hours is not going to prepare you well for a race that is going demand that you ride at 80 rpm for 2 hours and then 100 rpm for the last hour.

You just simply are not training specifically for the demands of the event. This is where quadrant analysis comes into play.

Scientific studies using a variety of techniques have found that threshold power (FTP) represents not only a threshold in terms of the power that an athlete can sustain, but also somewhat of a threshold in terms of fast-twitch fiber recruitment. To state it another way: When pedaling at a typical self-selected cadence, functional threshold power appears to occur at the power (and thus force) at which significant fast-twitch fiber recruitment first begins. Thus, not only does cardiovascular fitness play a role in your success, but so does your neuromuscular function.

Neuromuscular function sounds complicated, but it simply means how fast you can contract a muscle, how strongly you can contract it, and how long you can keep it contracted before relaxing it again.

Quadrant analysis plots

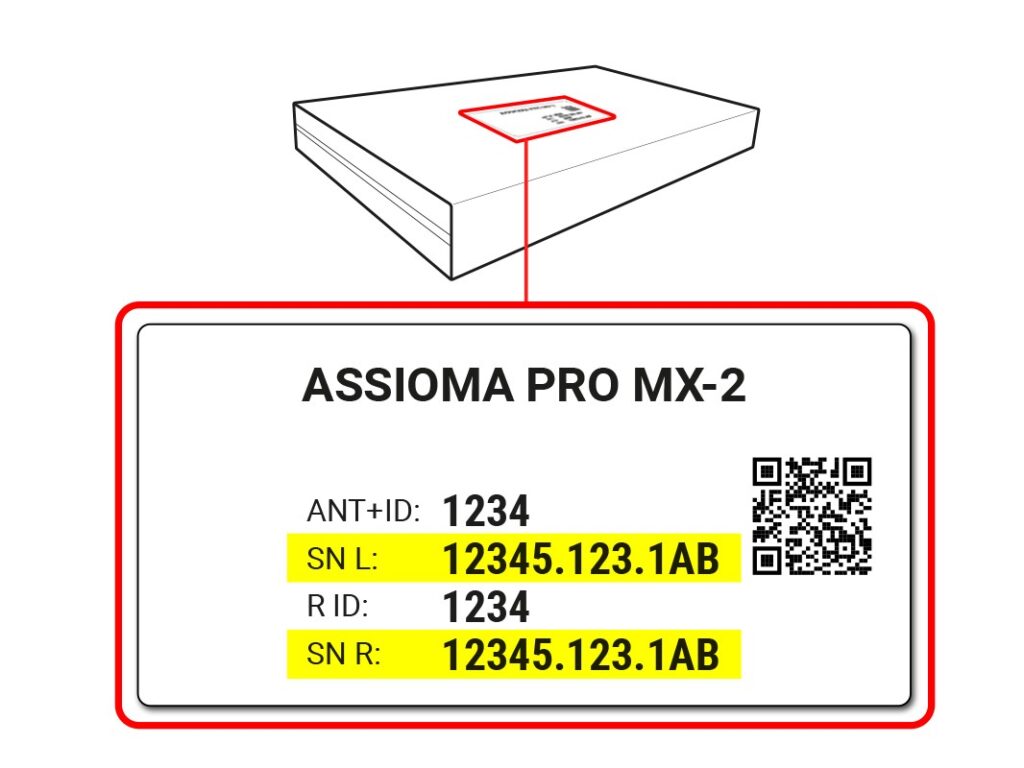

With a power meter like Assioma PRO MX and quadrant analysis, you can make sure that you are indeed training properly for the cardiovascular AND neuromuscular demands of your event. Enough of this physiology speak; let’s examine some different quadrant analysis plots so you can understand how to apply this in your own training.

1. The first plot is a plot showing you what a typical mountain bike race would look like.

Figure 1 shows how most of this race was spent in Quadrant II (high force, low cadence) and this is characteristic of a mountain bike race in which the rider has to keep a lower cadence to produce higher forces to maintain traction, pop over obstacles and power through sketch sections.

What about your training?

Does your Quadrant Analysis plot look the same from your training data as it does in your events?

This is where you really apply the concept of making appropriate changes to your training, so that you “train to the demands of the event”. Quadrant analysis is useful to first gain an understanding of just what the plots represent and then compare them to each other and to training.

2. Let’s examine another training session by a mountain biker who did a typical workout for him before coming to me for coaching.

We see in Figure 2, that he spent a lot of his time riding near his threshold power (all the points above the curved line in the middle of the chart, which is similar to racing in an MTB race), but he also spent the majority of time in Quadrant 1, which is faster than 90rpm and lower forces.

This is directly opposing Figure 1 where the typical MTB race power is created with slower than 90rpm and higher forces.

So, while this athlete was producing the correct wattage to stress his cardiovascular system, he was not “creating” power correctly to put the proper stress on his muscular system. This was something that we had to correct immediately in his training. He did most of his training on his road bike and after seeing the data, we decided to limit his cadence to 80 rpm during his FTP intervals on the flats and then at 60 rpm on the climbs.

This was a simple and easy fix that he could do on his road bike. We also increased by 1 day per week his training on his MTB and specifically made that a day when picked a harder more technical trail to not only hone his technical skills but also to pedal a slower cadence with higher force to ensure the creation of power in Quadrant 2.

Conclusions

In conclusion, it’s not just your cardiovascular output (FTP) that determines your success as a mountain biker but also your neuromuscular output or how you create the watts.

Each of us has strengths and weaknesses related to how we prefer to create the watts. Some like to pedal at a faster cadence and some of us prefer to use a slower cadence but push harder on the pedals and while neither is necessarily better or worse than the other, certain races and terrain demand more of one than another.

The key for you to understand is that when you train, you must train specifically for that event which has unique demands so that you will be ready for those demands.

If you need to be able to go up a 15% hill and do it in your 34-tooth cog, then you had better make sure you train in QII enough to be ready for that much muscular strength.

If you are going to do a flatter MTB race, then it’s important that you are ready for a sustained hard effort in QII and QIV, without any ‘recovery breaks’ in QIII.

Hunter Allen has FTP online training programs available at FTP Archives – Shop Peaks Coaching Group.

He is the co-author of “Training and Racing with a Power Meter”, “Cutting Edge Cycling” and “Triathlon Training with Power”.

They are available at www.shoppeaks.com.

You can contact Hunter directly at www.PeaksCoachingGroup.com for personal coaching and camps.